|

| The sunset from beautiful Kealakekua Bay. |

We could have stayed forever in Honomalino Bay, but there was no place to get water, so we headed to the next anchorage, Hookena.

As we entered the bay, a long rock wall with white letters spelling “Aloha” greeted us. We anchored next to a tall cliff riddled with holes and caves. The noise of the water echoed off the wall and back to us. Adjacent to the cliff is a beautiful beach with a popular campground and a dozen or so homes up from the beach.

It's hard to imagine now, but a century earlier Hookena was the major port in south Kona with regular visits from steam ships. We could see the remains of the old wharf and landing. In 1889 Robert Lewis Stevenson came to Hookena to escape the noise and confusion of Honolulu. While we were anchored here I read one of his short stories set partly in Hookena.

We visited the week before school started. There were lots of local families camping there, enjoying their last week of freedom. People are naturally curious about us when we come ashore. We often get peppered with questions. The most common is “What do you eat?” followed by “Do you sleep on your boat?” “How long did it take to sail here?” and “Are you scared?” We answer their questions and, if we like them, them to swim out and visit us, but this rarely happens.

The morning of our second day at Hookena, we looked out and saw three preteens (a brother, sister and the brother's friend) swimming to our boat. We recognized them as questioners from the day before and invited them aboard. We fed them cookies. The next day their older sister and mom swam out to visit us. It was a fun!

|

| Although found on reefs throughout the topical Pacific, yellow tangs must like Hawaii the best. There are so many of them Kona get's its nickname "The Gold Coast" from their great numbers. |

We enjoyed snorkeling every day at Hookena. The predominant fish is the ubiquitous yellow tang. There are so many on the Kona side of the Island of Hawaii that it is often called the Gold Coast. We even saw a rare color variant of a yellow tang that was mostly white. Some people call these ghost tangs.

|

| Ghost tang. |

We went scuba diving one day with our friend

Garry and two of his guests, Ginger and Grant from Texas. We started at the old ruins of the wharf and found interesting rock formations including an arch near the point. The coral is healthy and abundant and so are the reef fish. Virginia saw a reticulated butterflyfish, an octopus, a pair of lined butterflyfish the size of dinner plates and other of our favorite rare fish. Diving the Big Island is always a treat.

Most mornings we were greeted with a pod of dolphins swimming around the boat. They usually stayed a couple of hours jumping and spinning around our boat. Brandon would don fins and mask and join them in the clear water. He would stay in one spot and let the dolphins swim past him. Virginia usually preferred to watch them perched on the deck box. She felt she could see more of the action that way.

|

| Swimming with wild dolphins a Kealakekua Bay. |

Some people are weird about swimmers in the water with the spinner dolphins. We are strongly against chasing or harassing them in any way. If you quietly stay in one place the dolphins usually come to you. They seem as interested in us as we are in watching them. A couple of locals who frequent the beach told us that last winter the park was closed because of an outbreak of

Dengue Fever in the area. They admitted sneaking in while the park was closed and said they never saw the dolphins come into the bay to swim. Their opinion was the pod wasn't interested in visiting the bay when there are no swimmers to play with.

The Big Island is strict about staying anchored in the same place for more than 72 hours. We pushed our luck and stayed five days before we moved on.

|

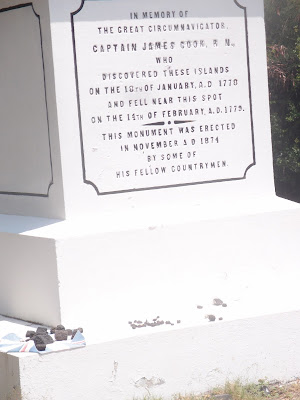

| The base of the Capt. Cook monument. |

Our next stop was Kealakekua Bay, best known as the place where Captain James Cook was killed in 1779. The main attraction to this bay is the Marine Conservation District in the north part of the bay and the monument memorializing the spot Cook died. The bay is rightly famous for its coral heads and many varieties of reef fish.

The first morning we were here, Virginia paddled over to the monument on the kayak. Brandon hung on to the back of the kayak for part of the way and swam part of the way from where we were anchored to the monument, about a mile. The effort was worth it. The coral and reef life near the monument was the most beautiful we have ever seen. Snorkel boats and guided groups of kayakers filled the water, but even that couldn't spoil the splendor of the surroundings.

You can't anchor or land a kayak anywhere in the marine conservation area near the monument, so we took turns: one of us staying with the kayak while the other climbed a badly-corroded steel ladder to view the Cook memorial.

Up to this point we hadn't encountered any other cruising boats in Hawaii, But we did meet an ex-cruiser while anchored at Kealakekua Bay. One afternoon, after returning from visiting the monument, a woman named Gretchen swam up to the boat and introduced herself, She said she cruised the South Pacific for a couple of years about a decade ago. We invited her aboard, handed her a towel, and had a wonderful visit. She now lives nearby Kealakekua, but she was born and raised on Kauai.

We enjoyed two beautiful sunsets and a very protected anchorage in Kealakekua Bay. There was almost no motion at night, almost like being in a marina -- not like most of the other anchorages that are open to waves and swell.

We weren't about to push our luck with the 72-hour rule at this anchorage and only stayed two nights then sailed on.

|

| Sunset at Kailua Kona. |

Our next stop was the busy town of Kailua Kona. We anchored just out of the harbor and next to a popular swimming lane. All day local people swam by our boat. Many of the swimmers would stop and visit with us. We enjoyed talking with them and several of them told stories about other boats who anchored without regard for the coral. They were impressed that Brandon always dove on the anchor to make sure it or the chain was not a danger to the coral.

Kailua Kona is the tourist hub of the Big Island and we enjoyed walking around this cute shops and historical sites. We ate some pretty good fish 'n chips at a restaurant with a great view of our boat. We also called our

Uber girl, Gigi, and arranged for a Costco run and to pick up other supplies.

|

| At anchor in rolly Kailua Kona. |

The anchorage is well known for being one of the most consistently uncomfortable anchorage in the islands. We are pretty tolerant of rolly anchorages and were comfortable for the first four days. Then the wind and waves started coming from different directions and we soon learned why no one stays long in Kailua Bay. We decided to leave the next morning.

Alas, our charmed life turned against us. Our engine didn't want to work well. We messed with it all day and got it to function well enough that we could leave the next morning. It wasn't working perfectly, but we were able to get out of the harbor, put up our sails and head to Nishimura Bay, which is on the north end of the Big Island.

There we would wait for fair winds to cross the

Alenuihaha Channel. This small bay had a rock wall and beautiful trees amid big lava rocks. Underwater was beautiful as well with plenty of coral and fish. We wished we had taken a picture but we didn't. The wind howled the two days we were anchored so we didn't dare go ashore or snorkel. We were safe in our little bay: while the water was calm in the anchorage, just outside we watched the white caps and big waves march by.

|

| Short drying time in windy Honomalino Bay. |

We finally met another cruising boat. They were a California couple who sailed their Hunter 45 sailboat to Hawaii four years ago. They now keep it in a Honolulu marina for most of the year while they are home in California and cruise the islands for a couple of months in the summer. They were headed to Hana on Maui. The day they left the winds looked wicked.

The U.S. Coast Guard warns the “channel is generally regarded as one of the most treacherous channels in the world because of strong winds and high seas.” The channel creates a venturi effect between two of the world's tallest mountains – on Maui, Haleakala and on Hawaii, Mauna Kea. The current generated by 2000 miles of trade winds is forced to funnel in between the two islands making for a strong current.

Our fair winds showed up the next morning, Aug. 16, and away we went. Like many of our passages, we were told how bad it would be. Once again, nothing evil happened and we actually enjoyed the windy sail to Maui. After all, why have such a great sailboat if you can't have wind to sail? Five hours later we dropped our anchor in a big sand patch at Big Beach on the south end of Maui.

|

| Crossing the Alenuihaha Chanel was a blast! |